Drill Evaluation Case #2: DB Square-up

Seems like I want to call out a bad drill, but that's not true.

I'll walk you through a clear grading process using the PATE Matrix—so you can begin seeing drills as learning environments, not just activities.

The video showed up in my Instagram feed (@rolfgoetz_flag). Variations of it are widely known and used by both American and Flag Football coaches:

The description accompanying it says it’s about staying square, i.e. keeping hips and shoulders parallel to the line of scrimmage, in front of the opponent. It also says it's about swiping down with both hands to pull the belt. It looks snappy, and the observer quickly "gets" what this is about. Ready to copy. I am not going to comment on the swiping, since they do not use IFAF regulation belts and flags, which would not allow the whole belt to come off.

3 Key Takeaways

See drills through a learning lens. PATE helps us ask not “Does it look good?” but “What is this teaching—and how?

E4 × T2 ≠ game prep. Even with solid movement or intensity, a drill with no real decisions or cues won’t translate well to live play.

Refinement beats replacement. You don’t need to scrap drills—subtle changes to pressure, opponent behavior, or decision context can dramatically elevate learning value.

2 Thought-Provoking Questions

If someone filmed your last three practices, which drill would not pass the PATE Gate—and why?

What’s one small constraint you could add to your favorite movement drill to make athletes think as well as move?

The Setup (Observed Drill)

Defending athlete starts directly in front of one stand-still opponent (1v1), pulls flags, shuffles a few feet to the next opponent. Repeat.

No live opponent, no task variation (in this video); the number of flag pulls is limited by the number of training partners

Focus appears to be on the specific movement quality or footwork: shuffling from side to side in order to keep the squared-up position

The speed of the athlete looks self-determined; stress levels depend on execution speed of the athlete, not the opponent

Note: This is not an assessment of the athlete’s performance or a judgment on the coach’s choices. Instead, it’s a clear-eyed look at the learning potential embedded in the setup. We’re working with partial information: two possible focus points (staying square, swiping down), but we don’t have insight into all criteria—like whether body height, hand usage, or spacing matter.

We also lack the full context. (It’s possible that later in the drill, opponents start to move.) We can’t say whether this is designed for development, evaluation, or something in between.

Step 1: Gate Check

Before using the Matrix, we first test the perception–action link. We ask:

Is there a live, game-relevant cue? → ❌ No, opponents do not appear in predictable positions in games.

Does the athlete make a real-time decision? → ❌ No, since the opponents are basically dummies with flags.

Does that decision change the outcome of the rep? → ❌ No, no decision.

❌ Result: This setup doesn’t cross the Gate threshold.

We’ll continue scoring the drill, but only as an illustrative case—not a recommended one.

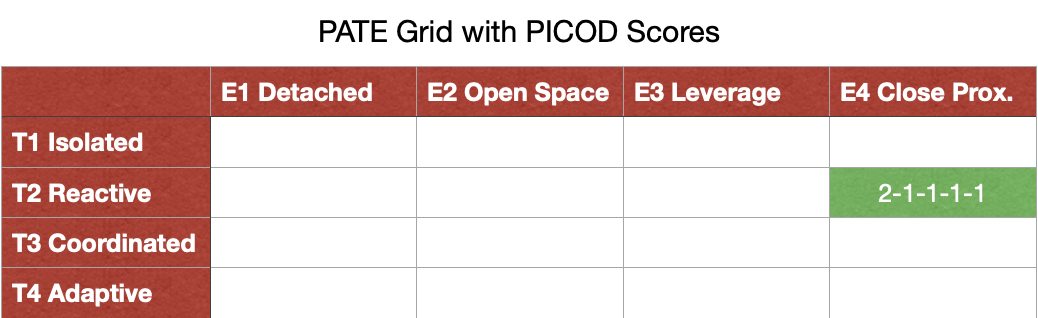

Step 2: Engagement Format — E4 (Close Proximity)

The defender is physically close to another athlete.

Tagging is within legal contact range.

This aligns with the criteria for E4: Close Proximity, such as a short-range flag pull near the goal line.

Step 3: Tactical Load — T1 (Minimal Load)

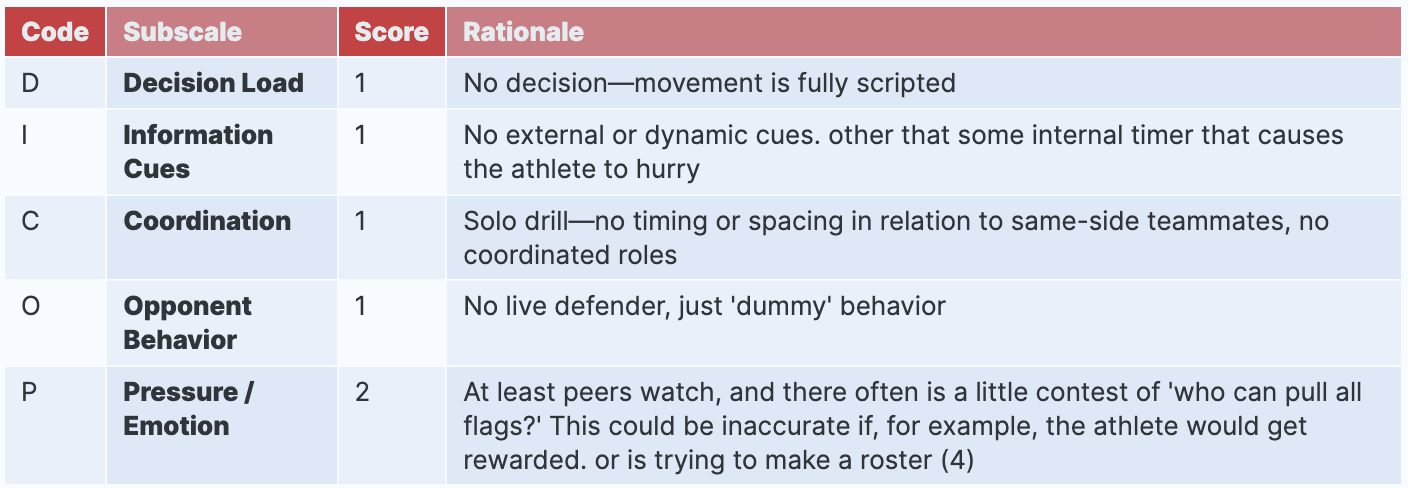

So this is the verdict for the clip we just saw:

Highest Subscore: 2 → Tactical Load Row = T2

So we arrive at this evaluation of the repetition shown in the video:

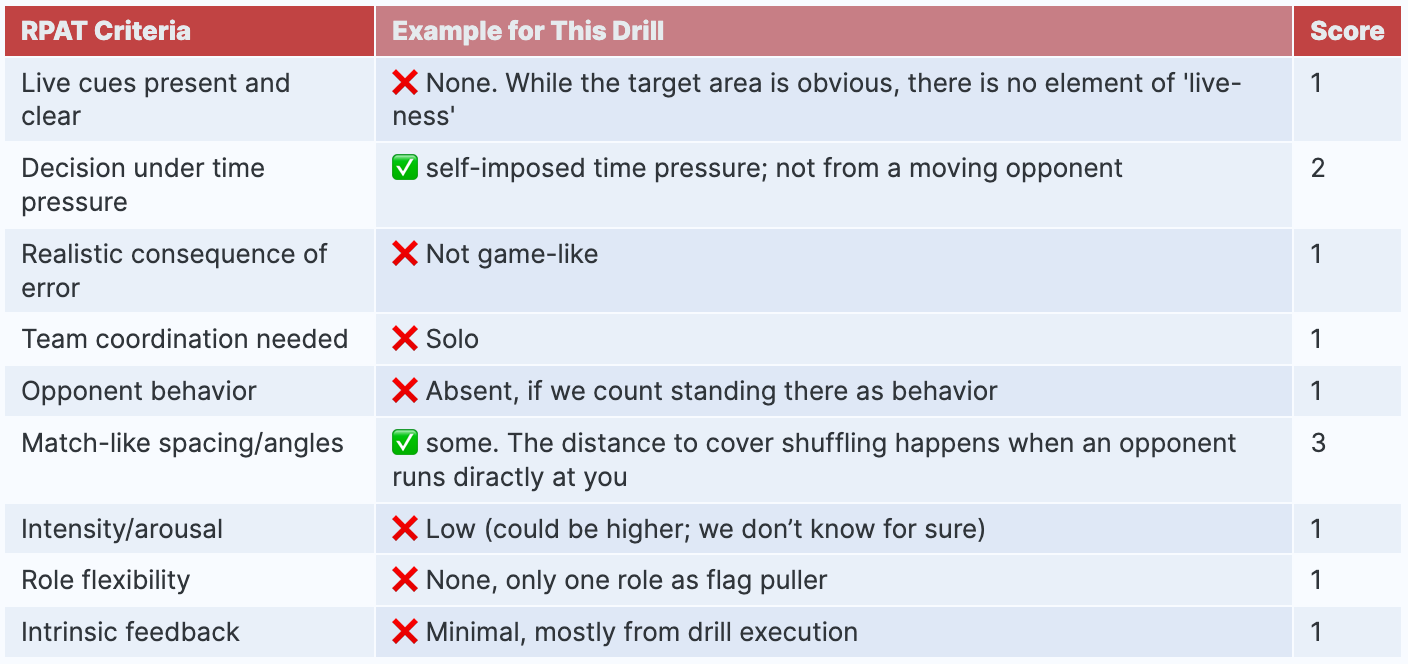

Step 4: RPAT Sanity Check (optional)

Running the RPAT tool confirms our matrix estimate:

Total: 12 / 36 → This result indicates limited representativeness. If the goal is game readiness, the design would need major upgrades.

Coaches often describe similar drills as focused on movement fundamentals or fine-tuning technique. That’s a hallmark of linear pedagogy—start with isolated technique, then layer in complexity.

But that sequence is increasingly under scrutiny. Research suggests that nonlinear learning—introducing variability from the start—leads to better retention and stronger skill transfer.

There’s a great episode of Rob Gray’s Perception-Action Podcast where he discusses yet another scientific study showing that starting with “the fundamentals” is neither necessary nor superior to a nonlinear approach to skill development.

Summary: Why This Drill Maps to E4 × T2

This drill doesn’t reflect live game conditions.

Still, it might serve other aims: warming up, honing basic motor patterns, or assessing basic movement traits.

But for transfer?

No decisions required

No cues to interpret

No adaptive behavior

No tactical implications

Some pressure from peers or coaches, but no consequence for decisions

That’s what an E4 × T2 rating communicates: a task with limited cognitive or contextual challenge—even if it looks crisp.

My rule? Let athletes do this kind of drill once or twice, then shift to something that demands more: perception, adjustment, timing. Maybe this coach did exactly that.

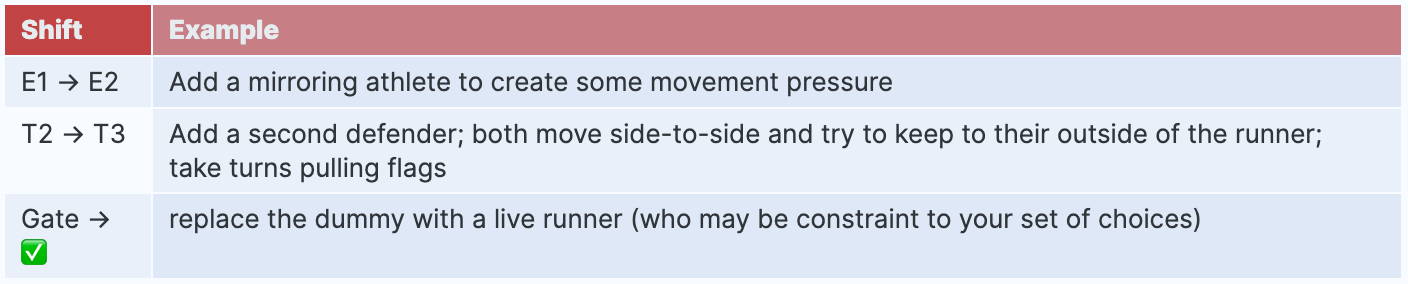

What Might Shift It?

If you’re aiming for transferable skill, small nudges can make a big difference:

Each tweak adds a layer of perception or response—without needing to reinvent the whole drill.

Try changing just one PICOD sub-score. For instance:

Add a scoring rule or timer to raise stakes

Let the attacker break direction at random, forcing reactive movement

Pair defenders who must work together to close down angles

Add multiple potential attackers, requiring recognition and choice

These aren’t major overhauls. But they shift the learning landscape.

If you want a full walkthrough on this idea, I wrote a post on upgrading your drills with the PATE Matrix and nonlinear pedagogy.

Final Note

This isn’t about “gotcha” coaching critique.

It’s about learning to see clearly—to understand what’s really being trained, and how to evolve your sessions accordingly.

Download the PATE Evaluation Form here → Coach Pack

Want help decoding a drill? Send me a clip. I’d love to walk through it with you.

My goal is simple: to help more coaches gain a sharper lens on practice. Not for perfection—but for progress. The Matrix isn’t a tool to tear things down. It’s a guide to building up smarter.

And if even one coach sees an old drill in a new way because of this work? That’s already a win.

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to stay updated on deeper insights about navigating change in both business and sports.

Why not work with Rolf?

Rolf is a seasoned performance coach and coach developer, with a unique perspective that challenges conventional thinking. He works across both the business and sports worlds, supporting teams and individuals through change. Currently, he coaches multiple teams and provides personalized guidance to leaders in both fields.

📌 PS: If you found this post helpful, would you please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience? This post is public, so feel free to share and forward it.

LinkedIn

Instagram

Email: info@flag-academy.com

Email: rolf@beyondchampionships.eu

Facebook: Coaching Beyond Championships