Coaches collect drills the way readers stash books. We line them up on mental shelves, pull out favourites, lend them to friends. Then, on a quiet car drive home, the question creeps in: Did that six‑cone zig‑zag actually make my players better at the game—or just better at the drill?

In the next five minutes you’ll know exactly how to tell.

Quick PATE Matrix primer:

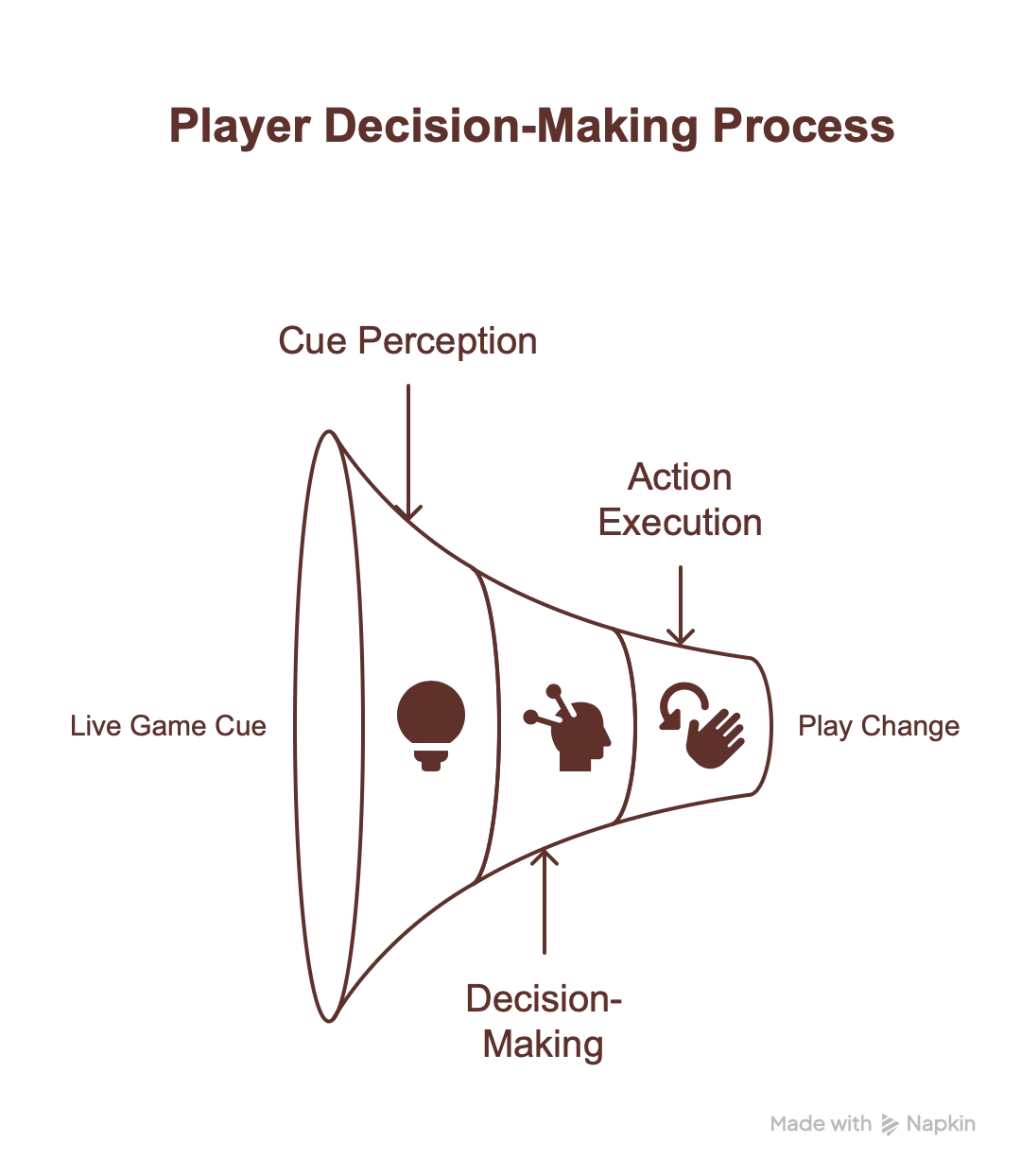

P — Perception–Action Coupling (Matrix Gate) ❓ See → decide → act?

A — Athlete (focus)

T — Tactical Load (rows)

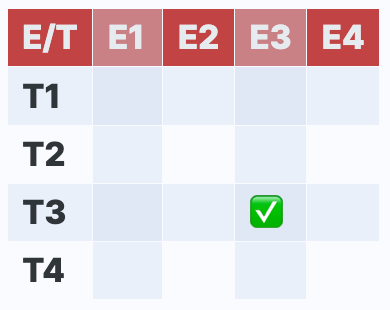

E — Engagement Format (columns)Drills only enter a 4 × 4 grading grid after they clear P. Then you place them by tactical + engagement levels.

The Drill‑Design Fog — Why Smart Coaches Still Miss the Mark

Myth #1 — “More cones = more skill.” Add landmarks, design a tight choreography, keep instructing—skill must rise… right?

Myth #2 — “Repetition creates muscle memory.” Hammer the same move out of context and the body will magically stitch it into the match.

Modern motor‑learning research says otherwise: practice must keep the information–action link intact or the nervous system encodes choreography, not sport (Renshaw et al., 2019; Baker & Young, 2014). That finding echoes the play‑to‑practice pathway outlined by Côté, Baker, & Abernethy (2003). Also, a meta-analysis found deliberate practice explains < 20 % of performance variance once context is stripped away (Macnamara, Moreau, & Hambrick, 2016).

What you’ll walk away with today

A single yes/no Matrix Gate you can run on any drill in under 30 seconds.

A clear 4 × 4 picture of why and how reality‑rich practice sticks.

A mini challenge you can test at tomorrow’s session.

So how do we slice through the fog?

Enter the PATE Matrix

PATE is a 4 × 4 grid where qualified drills live. Qualified means they first clear the Matrix Gate—the question of whether athletes see → decide → act in real time. Once through, you anchor it to the grid like this:

P — Perception–Action Coupling (the Matrix Gate you just cleared)

A — Athlete, the focus of skill development (rows)

T — Tactical load (rows)

E — Engagement format (columns)

CLA coaches, breathe easy—the Matrix is simply your favourite task and environmental constraints rendered in four‑step glory (Renshaw et.al., 2019; Davids, Otte, & Rothwell, 2021). It also echoes the ecological-dynamics view that skill emerges from constant performer–environment coupling (Renshaw et al., 2023).

Soccer, football, basketball, rugby, lacrosse—the axes work for any invasion game. (Volley or combat coach? Stick around; you’ll see how to adapt.)

The Matrix Gate — The Game‑Transfer Filter

Matrix Gate question: “Does every player see a live, game‑relevant cue, decide in that moment, and act so the decision changes the play?”

Matrix Gate Checklist

Representative Learning Design shows that when checklist items one to three are present, learning sticks; sever them and improvement stalls (Renshaw et al., 2019). Adding the item of Emotional Load is supported by Headrick et al. (2015) and Lindsay & Spittle (2024).

Quick Snapshot — What Fails vs Passes the Gate

Why the Matrix Gate Matters — Evidence & Pay‑offs

Comprehensive reviews of elite coaching agree that representative tasks accelerate expertise (Farrow, Baker, & MacMahon, 2013). The main factors for representativeness include:

Retention: Drills preserving information–action coupling hold skills longer than isolated reps (Renshaw et al., 2019).

Emotion: Built‑in competition accelerates self‑regulation and motivation (Headrick et al., 2015).

Decision Speed: Live‑cue practice improves option generation under 400 ms vs > 700 ms in blocked variants (Orth et al., 2018).

Adaptability: Representative multi‑agent practice fosters flexible team coordination (Passos et al., 2009). Viewing teams as complex adaptive systems underscores the need for constraint-rich tasks (Davids, 2021).

Isolated drills can speed early skill acquisition but, if over-used, have poor game-transfer; coaches should move toward more representative practice as soon as feasible. — Lindsay & Spittle (2024)

Practical wins: clarity in planning, a common language for staff, built‑in progressions (return-to-play and periodization).

Preview: Engagement & Tactical Axes

Think of the grid as an X‑Y map: E‑columns track physical closeness & competitive heat, T‑rows track decision traffic & tactical messiness.

Engagement (E1–E4): From detached to open‑space to leverage‑based to close‑proximity scenarios.

Tactical Load (T1–T4): From isolated to reactive to coordinated to adaptive decision chains.

Stay tuned—the full scoring rubrics for both dimensions drop next week.

Mini Case Studies

Flag Football – Why it Works

Live cue: Ball‑carrier changes speed/direction under pressure.

Decision: Defender picks angle & timing; attacker chooses feint or cut.

Fidelity & emotion: Goal‑line stakes, full‑speed contact‑free pull.

What E3 × T3 means: Leverage‑based engagement (E3) where bodies contest the same tight space, plus a coordinated decision chain (T3) that forces both players to layer fakes, footwork, and timing—not just react once.

Basketball – Why it Works

Live cue: On‑ball defender pressure and rotating help defender.

Decision: Ball‑handler chooses drive, kick, or pull‑up; shooters relocate.

Fidelity & emotion: Shot clock, score‑tracking, and physical contact mimic real half‑court possession.

What E3 × T3 means: Leverage‑based contact (E3) with shoulder‑to‑chest drives, plus a coordinated decision chain (T3) as offence and defence trade rotations, kicks, and close‑outs in real time.

Different courts, same logic: once the live information stream, adaptive decision, and meaningful outcome are in place, the drill locks into the high‑value centre of the grid.

Try This Tonight — 30‑Second Coach Challenge 🙃

Grab your sacred‑cow drill from tomorrow’s plan.

Run the Matrix Gate checklist.

If it fails, tag it warm‑up/technique and plug in a Gate‑passer.

Drop your results in the comments—brag or roast welcome.

Up Next

Next week we’ll grade any drill in under 60 seconds, unveil the full rubrics for both the Engagement and Tactical axes, and hand you a simple 1‑page scoring sheet. Stay tuned.

Further Reading

Baker, J., & Young, B. (2014). 20 years later: Deliberate practice and the development of expertise in sport. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7_(1), 135‑157. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2014.896024

Côté, J., Baker, J., & Abernethy, B. (2003). From play to practice: A developmental framework for the acquisition of expertise in team sport. In J. Starkes & K. A. Ericsson (Eds.), Expert performance in sports: Advances in research on sport expertise (pp. 89‑113). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Davids, K., Otte, F., & Rothwell, M. (2021). Adopting an ecological perspective on skill performance and learning in sport. European Journal of Human Movement, 46. https://doi.org/10.21134/eurjhm.2021.46.1

Davids, K. (2021). _Athletes and sports teams as complex adaptive systems: A review of implications for learning design. _RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 17 (66), 18-34. https://doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2021.06602

Farrow, D., Baker, J., & MacMahon, C. (Eds.). (2013). Developing sport expertise: Researchers and coaches put theory into practice (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Headrick, J., Renshaw, I., Davids, K., Pinder, R., & Araújo, D. (2015). The dynamics of expertise acquisition in sport: The role of affective learning design. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 83‑90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.006

Lindsay, R., & Spittle, M. (2024). The adaptable coach – a critical review of the practical implications for traditional and constraints‑led approaches in sport coaching. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 19(3), 1240‑1254. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541241240853

Macnamara, B. N., Moreau, D., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2016). The relationship between deliberate practice and performance in sports: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 333-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635591

Orth, D., Kamp, J., & Button, C. (2018). Learning to be adaptive as a distributed process across the coach–athlete system. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(2), 146‑161. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1557132

Passos, P., Araújo, D., Davids, K., Gouveia, L., Serpa, S., Milho, J., & Fonseca, S. (2009). Interpersonal pattern dynamics and adaptive behavior in multi‑agent neurobiological systems. Journal of Motor Behavior, 41(5), 445‑459. https://doi.org/10.3200/35‑08‑061

Renshaw, I., Davids, K., Araújo, D., Lucas, A., Roberts, W., & Newcombe, D. (2019). Evaluating weaknesses of “perceptual‑cognitive training” and “brain training” methods in sport: An ecological dynamics critique. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02468

Renshaw, I., Davids, K., O’Sullivan, M., Maloney, M., Crowther, R., & McCosker, C. (2023). An ecological dynamics approach to motor learning in practice: Reframing the learning–performing relationship in high-performance sport. Asian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 3_(4), 100181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsep.2022.10.004

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to stay updated on deeper insights about navigating change in both business and sports.

📌 PS: If you found this post helpful, would you please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience? This post is public, so feel free to share and forward it.

Rolf is a seasoned performance coach and coach developer, with a unique perspective that challenges conventional thinking. He works across both the business and sports worlds, supporting teams and individuals through change. Currently, he coaches multiple teams and provides personalized guidance to leaders in both fields.

LinkedIn

Instagram

Email: info@flag-academy.com

Email: rolf@beyondchampionships.eu

Facebook: Coaching Beyond Championships

Really like this!! Can’t wait for the volleyball version!!