The Kind of Coach I Want to Be

Not the one with the perfect explanation. The one who sees what the moment needs.

We were working with our U13s on defending space, not people. The usual pattern is familiar: kids follow the person in front of them, eyes locked on the QB rather than lanes, and the whole defense collapses the moment the ball moves, because two receivers were not capped. I didn’t explain much. I just marked three zones with cones and told them, “No one leaves their box unless they’re sure the ball is coming.” Then I let them play.

The first few reps were messy. Two players froze. One chased instinctively. A touchdown happened. By the third try something shifted. They started signaling to each other without me prompting it—a hand flick, a head nod, a small step that closed a passing lane just in time. You could feel them owning the defense, not performing it for me. They adjusted to the flow because the problem was visible to them, not described by me.

Nobody in that moment needed a lecture on “perception-action coupling.” They needed a chance to see the problem arise and decay in real time. And they did (also see: Three Hours, No Lines, All Learning).

That moment stays with me because it contradicts a story we hear everywhere—that understanding must be given before skill can emerge. But here, understanding grew from trying, failing, sensing, and coordinating.

And this is where the conversation about coaching theory usually begins to bend.

3 Key Takeaways:

No single coaching theory explains learning in a live, changing environment. The field shifts too quickly for rigid methods. Coaching happens in uncertainty, not certainty.

Traditional and ecological coaching are tools, not rivals. Structure builds stability. Constraints build adaptability. The craft is knowing which lever to pull.

Progress begins with noticing what the athlete struggles with. Perception? Decision? Coordination? Pressure? Design from that. Adjust lightly. Let learning emerge.

2 Thought-Provoking Questions:

Where in my sessions do players wait for me to think for them? What could I change so the problem becomes visible to them instead?

If I stopped trying to prove that my preferred approach is “right,” what would I start to notice in front of me that I’ve been missing?

The Problem with Choosing Sides

Almost everywhere you look, coaching is still shaped by the traditional model: explain, demonstrate, repeat. It’s visible. It’s teachable. It fits into clipboards, sessions plans, and YouTube tutorials. And because it’s the default, it becomes identity. “This is coaching.” So when something like ecological dynamics enters the room, it feels like an attack rather than an invitation.

Brian Klaas’s argument helps explain why. When we work in complex human systems, it’s almost impossible to prove that one theory is universally better. The world of athletes isn’t controlled. There are no stable control groups. Two 13-year-olds who look identical on paper will respond differently to the same cue, drill, or environment. The moment changes the outcome.

So instead of settling the debate through evidence, coaches form camps and defend their way. The arguments are rarely about what actually happens on the field. They are about identity, tradition, and feeling safe in what you already know.

But when the environment itself is unpredictable, certainty is a poor guide. What matters is whether a coach can notice what the moment needs and respond. Sometimes that’s direct instruction. Sometimes it’s constraint-led exploration. Sometimes it’s silence.

The real skill is choosing the next useful adjustment.

Let’s talk about what choosing looks like in practice.

Expanding the Toolbox

Most coaches are good at structure. They know how to organize a practice, break skills down, and give corrections that make athletes feel supported. That’s a strength—not something to discard. The trouble begins when structure becomes the only way a coach knows how to create learning.

When every session follows the same pattern: explanation, demonstration, drill, correction—players learn to wait. They wait to be told what to notice, what to try, what is right. It works well for stability. It struggles when the game demands adaptability.

This is where ecological coaching adds value. It doesn’t replace structure. It adds a second set of tools. Tools for helping players:

Read space instead of remembering instructions

Coordinate with teammates when plans break

Adapt under pressure rather than replicate technique

Solve new problems rather than rehearse old ones

You don’t need to become a different kind of coach. You don’t need to abandon what you already do well. You only need to add one more lever to pull.

One small shift is enough to start:

Instead of explaining the solution first, expose the problem.

Let the players feel what needs to change.

Then guide the adjustment.

This isn’t ideology. It’s design.

And once you see players solve something on their own—even once—it changes how you coach forever.

From Theory Wars to Real Problems

When coaches talk about “traditional” versus “ecological,” the debate often sounds like a choice between two belief systems. But in reality, the coaching environment looks much more like the world Brian Klaas describes: a complex system with too many moving parts to isolate one “correct” method.

In a real practice, you never control all variables:

One player slept poorly.

Another is growing fast and feels uncoordinated.

One is shy today because of school.

A teammate is missing.

The weather changes the ball flight.

Confidence rises, falls, and rises again.

The learning environment is never the same twice.

So the question is not:

Which theory explains everything?

The question is:

What is the obstacle in front of this athlete, in this moment?

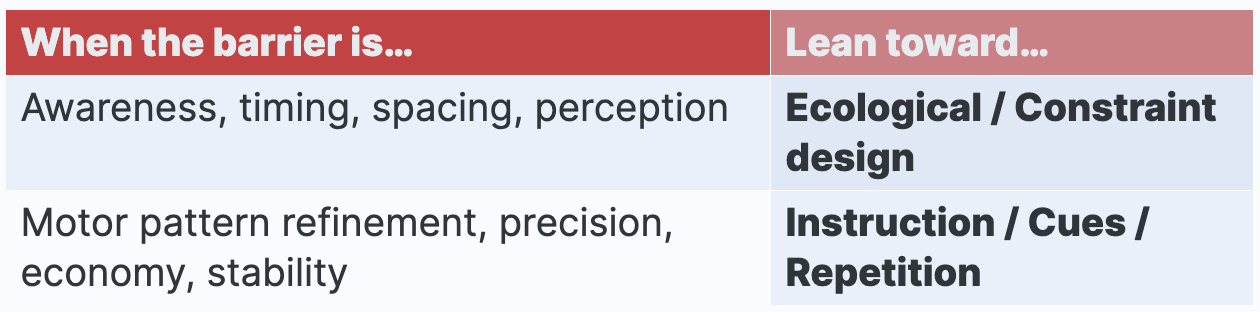

Once you see that, the choice of coaching strategy becomes clearer:

If the player doesn’t see the game problem, you design a constraint that makes the problem visible.

If the player sees it but can’t coordinate the movement, you offer a cue, a reference point, or a rhythm.

If the player executes well but fails under pressure, you add stakes, timing, or opponent behavior.

You are not choosing a theory.

You are choosing the next useful condition.

This is where the two toolsets meet:

The job is not to be a “constraints coach” or a “traditional coach.”

The job is to be a coach who can diagnose and select.

And once you see it that way, the entire debate loses its heat.

What matters is helping players become more capable in real games—not defending a method.

🙋♂️

If something I made helped you in any way, however small, I’d love to hear what changed or what you built with it. That reflection is what keeps this work breathing.

Coaching as Craft Under Uncertainty

If learning is unpredictable and players are not identical, then coaching isn’t about applying the right theory. It’s about designing conditions that make useful adaptations more likely.

That’s a craft, not a doctrine.

Craft means:

Watching carefully.

Adjusting lightly.

Knowing when to step in, and when to let things breathe.

No model gives certainty here. But better questions help:

What is the player failing to perceive?

What decision are they avoiding or rushing?

What coordination breaks under pressure?

Once you can answer those, you don’t need to decide which philosophy is “correct.” You decide what to do next:

Adjust the task (space, time, numbers, scoring).

Add or remove information.

Offer one short cue, then return to silence.

Let the game expose the problem again.

The aim is simple:

More moments where players solve things themselves.

Fewer moments where we solve the game for them.

This is not switching theories. It’s widening your field of view.

And capacity is what players feel — on the field, in motion, with others.

Closing

If we accept that coaching takes place in a moving, living system, then arguments about which theory is “right” will always stall. There is no clean control group in sport. No stable baseline. Every player is a changing person in a changing environment.

So the goal isn’t to prove a philosophy, but to increase our ability to respond to what’s actually happening.

Traditional coaching gives us structure and clarity.

Ecological coaching gives us adaptability and perception.

The skill is knowing when to use which.

If we can help players see better, decide better, and coordinate better under pressure, then we’re doing the work. That’s the only measure that matters.

Not theory victory.

Not ideological purity.

Just better players in real games.

The mission isn’t conversion.

It’s range.

Coaches who can see more possibilities create athletes who can do the same.

A Note Back to Klaas

Brian Klaas points out that in complex human systems, theories rarely die—not because they’re correct, but because they can’t be cleanly proven wrong. Coaching lives in the same terrain. The environment shifts every minute, and we can’t isolate variables the way we can in a lab. So debates about which coaching philosophy is “right” will always outgrow the available evidence.

Once you see that, the argument stops being about truth, and starts being about usefulness.

We don’t need a victorious theory.

We need working tools.

One Practical Step to Start

Pick one activity you already run every week.

Keep the players, the space, the ball, the rules.

Change just one condition:

Shrink or stretch the space

Add one defender

Give the offense a time limit

Award points for a specific behavior (e.g., “pass completed in stride”)

Run it. Say little. Watch what solutions emerge.

Then make a single adjustment.

That is ecological coaching in its simplest form:

not ideology — design, observation, adjustment.

🌀

What’s the first idea this unlocked for you? Leave it in the comments, please, or send me a quick message. I don’t want what I publish to vanish into the void.

Rolf is a non-linear pedagogy advocate, author, and coach developer from Germany. He writes about humane coaching, purposeful change, and the road toward dreams worth chasing.

If his work resonates, why not walk a stretch of the road with him?

📌 PS: If you found this post helpful, would you please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience? This post is public, so feel free to share and forward it.

My Payhip Store

I love coffee ;-)

LinkedIn

Instagram

Email: info@flag-academy.com

Email: rolf@beyondchampionships.eu

Facebook: Coaching Beyond Championships

Related Reading:

The Illusion of Control - Why coaches mistake regression to the mean for effective feedback (and what Kahneman’s Air Force story teaches us)

Game First, Not Drill First - What the Research Really Shows - What science says about linear vs. non-linear practice design

Three Hours, No Lines, All Learning - How a three-hour session against first-league players taught through continuous play and constraint manipulation